Church Committee

The Church Committee (formally the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities) was a US Senate select committee in 1975 that investigated abuses by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), National Security Agency (NSA), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Chaired by Idaho Senator Frank Church (D-ID), the committee was part of a series of investigations into intelligence abuses in 1975, dubbed the "Year of Intelligence", including its House counterpart, the Pike Committee, and the presidential Rockefeller Commission. The committee's efforts led to the establishment of the permanent US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.

The most shocking revelations of the committee include Operation MKULTRA, which involved the drugging and torture of unwitting US citizens as part of human experimentation on mind control;[1][2] COINTELPRO, which involved the surveillance and infiltration of American political and civil-rights organizations;[3] Family Jewels, a CIA program to covertly assassinate foreign leaders.[4][5][6][7]

It also unearthed Project SHAMROCK, a program in which the major telecommunications companies shared their traffic with the NSA, and officially confirmed the existence of this signals intelligence agency to the public for the first time.

Background

[edit]By the early years of the 1970s, a series of troubling revelations had appeared in the press concerning intelligence activities. First came the revelations by Army intelligence officer Christopher Pyle in January 1970 of the US Army's spying on the civilian population[8][9] and Senator Sam Ervin's Senate investigations produced more revelations.[10] Then on December 22, 1974, The New York Times published a lengthy article by Seymour Hersh detailing operations engaged in by the CIA over the years that had been dubbed the "family jewels". Covert action programs involving assassination attempts on foreign leaders and covert attempts to subvert foreign governments were reported for the first time. In addition, the article discussed efforts by intelligence agencies to collect information on the political activities of US citizens.[11]

The creation of the Church Committee was approved on January 27, 1975, by a vote of 82 to 4 in the Senate.[12][13]

Overview

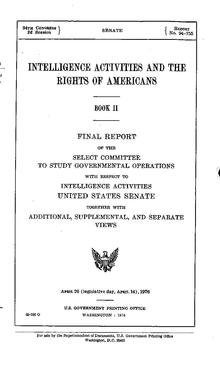

[edit]The Church Committee's final report was published in April 1976 in six books. Also published were seven volumes of Church Committee hearings in the Senate.[14]

Before the release of the final report, the committee also published an interim report titled "Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders",[15] which investigated alleged attempts to assassinate foreign leaders, including Patrice Lumumba of Zaire, Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic, Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam, Gen. René Schneider of Chile, and Fidel Castro of Cuba. President Gerald Ford urged the Senate to withhold the report from the public, but failed,[16] and under recommendations and pressure by the committee, Ford issued Executive Order 11905 (ultimately replaced in 1981 by President Reagan's Executive Order 12333) to ban US sanctioned assassinations of foreign leaders.

In addition, the committee produced seven case studies on covert operations, but only the one on Chile was released, titled "Covert Action in Chile: 1963–1973".[17] The rest were kept secret at CIA's request.[14]

According to a declassified National Security Agency history, the Church Committee also helped to uncover the NSA's Watch List. The information for the list was compiled into the so-called "Rhyming Dictionary" of biographical information, which at its peak held millions of names—thousands of which were US citizens. Some prominent members of this list were Joanne Woodward, Thomas Watson, Walter Mondale, Art Buchwald, Arthur F. Burns, Gregory Peck, Otis G. Pike, Tom Wicker, Whitney Young, Howard Baker, Frank Church, David Dellinger, Ralph Abernathy, and others.[18]

But among the most shocking revelations of the committee was the discovery of Operation SHAMROCK, in which the major telecommunications companies shared their traffic with the NSA from 1945 to the early 1970s. The information gathered in this operation fed directly into the Watch List. In 1975, the committee decided to unilaterally declassify the particulars of this operation, against the objections of President Ford's administration.[18]

Together, the Church Committee's reports have been said to constitute the most extensive review of intelligence activities ever made available to the public. Much of the contents were classified, but over 50,000 pages were declassified under the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992.

Committee members

[edit]| Majority (Democratic) | Minority (Republican) |

|---|---|

|

|

- Members of the Church Committee

Investigation into the assassination of John F. Kennedy

[edit]The commission also carried out an investigation into the November 22, 1963, assassination of John F. Kennedy, questioning 50 witnesses and accessing 3,000 documents. It focused on the actions of the FBI and CIA, and their support for the Warren Commission.

The Church commission raised the question of the possible connection between the plans to assassinate political leaders abroad, particularly in Cuba, and that of the 35th President of the United States.[19]

The Church Commission questioned the processes for obtaining information, blaming federal agencies for failing in their duties and responsibilities and concluding that the investigation into the assassination had been deficient.[19]

It participated in the creation of the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA), the second major investigation of the JFK assassination, from 1976 to 1979.[20]

Opening mail

[edit]The Church Committee learned that, beginning in the 1950s, the CIA and Federal Bureau of Investigation had intercepted, opened and photographed more than 215,000 pieces of mail by the time the program (called "HTLINGUAL") was shut down in 1973. This program was all done under the "mail covers" program (a mail cover is a process by which the government records—without any requirement for a warrant or for notification—all information on the outside of an envelope or package, including the name of the sender and the recipient). The Church report found that the CIA was careful about keeping the United States Postal Service from learning that government agents were opening mail. CIA agents moved mail to a private room to open the mail or in some cases opened envelopes at night after stuffing them in briefcases or in coat pockets to deceive postal officials.[21]

The Ford administration and the Church Committee

[edit]On May 9, 1975, the Church Committee decided to call acting CIA director William Colby. That same day Ford's top advisers (Henry Kissinger, Donald Rumsfeld, Philip W. Buchen, and John Marsh) drafted a recommendation that Colby be authorized to brief only rather than testify, and that he would be told to discuss only the general subject, with details of specific covert actions to be avoided except for realistic hypotheticals. But the Church Committee had full authority to call a hearing and require Colby's testimony. Ford and his top advisers met with Colby to prepare him for the hearing.[22] Colby testified, "These last two months have placed American intelligence in danger. The almost hysterical excitement surrounding any news story mentioning CIA or referring even to a perfectly legitimate activity of CIA has raised a question whether secret intelligence operations can be conducted by the United States."[23]

Results of the investigation

[edit]On August 17, 1975 Senator Frank Church appeared on NBC's Meet the Press, and discussed the NSA, without mentioning it by name:

In the need to develop a capacity to know what potential enemies are doing, the United States government has perfected a technological capability that enables us to monitor the messages that go through the air. (...) Now, that is necessary and important to the United States as we look abroad at enemies or potential enemies. We must know, at the same time, that capability at any time could be turned around on the American people, and no American would have any privacy left: such is the capability to monitor everything—telephone conversations, telegrams, it doesn't matter. There would be no place to hide.

If this government ever became a tyranny, if a dictator ever took charge in this country, the technological capacity that the intelligence community has given the government could enable it to impose total tyranny, and there would be no way to fight back because the most careful effort to combine together in resistance to the government, no matter how privately it was done, is within the reach of the government to know. Such is the capability of this technology. (...)

I don't want to see this country ever go across the bridge. I know the capacity that is there to make tyranny total in America, and we must see to it that this agency and all agencies that possess this technology operate within the law and under proper supervision so that we never cross over that abyss. That is the abyss from which there is no return.[24][25]

Aftermath

[edit]As a result of the political pressure created by the revelations of the Church Committee and the Pike Committee investigations, President Gerald Ford issued Executive Order 11905.[26] This executive order banned political assassinations: "No employee of the United States Government shall engage in, or conspire to engage in, political assassination." Senator Church criticized this move on the ground that any future president could easily set aside or change this executive order by a further executive order.[27] Further, President Jimmy Carter issued Executive Order 12036, which in some ways expanded Executive Order 11905.[26]

In 1977, the reporter Carl Bernstein wrote an article in the Rolling Stone magazine, stating that the relationship between the CIA and the media was far more extensive than what the Church Committee revealed. Bernstein said that the committee had covered it up, because it would have shown "embarrassing relationships in the 1950s and 1960s with some of the most powerful organizations and individuals in American journalism."[28]

R. Emmett Tyrrell Jr., editor of the conservative magazine The American Spectator, wrote that the committee "betrayed CIA agents and operations." The committee had not received names, so had none to release, as confirmed by later CIA director George H. W. Bush. However, Senator Jim McClure used the allegation in the 1980 election, when Church was defeated.[29]

The Committee's work has more recently been criticized after the September 11 attacks, for leading to legislation reducing the ability of the CIA to gather human intelligence.[30][29][31][32] In response to such criticism, the chief counsel of the committee, Frederick A. O. Schwarz Jr., retorted with a book co-authored by Aziz Z. Huq, denouncing the Bush administration's use of 9/11 to make "monarchist claims" that are "unprecedented on this side of the North Atlantic".[33]

In September 2006, the University of Kentucky hosted a forum called "Who's Watching the Spies? Intelligence Activities and the Rights of Americans", bringing together two Democratic committee members, former Vice President of the United States Walter Mondale and former US Senator Walter "Dee" Huddleston of Kentucky, and Schwarz to discuss the committee's work, its historical impact, and how it pertains to today's society.[34]

See also

[edit]- FBI–King suicide letter

- Hope Commission (established to investigate Australia's intelligence agencies)

- Hughes–Ryan Amendment

- Human rights violations by the CIA

- JFK Assassination

- Operation Gladio (included in the classified part of the report)

- Operation Mockingbird

- Presidential Emergency Action Documents

- Project Mockingbird

- The Shadow Factory

- Surveillance abuse

- Unethical human experimentation in the United States

- Special Activities Center (CIA)

References

[edit]- ^ "The Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, Foreign and Military Intelligence". Church Committee report, no. 94-755, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. 1976. p. 392. Archived from the original on June 26, 2003.

- ^ "Project MKULTRA, The CIA'sProgram Of Research InBehavioral Modification" (PDF). August 3, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 2, 2019.

- ^ "Intelligence Activities and the Rights of Americans – Church Committee final report. II" (PDF). US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. United States Senate. April 26, 1976. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 16, 2015.

- ^ "The CIA's Family Jewels". National Security Archive, George Washington University. May 16, 1973. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "A glimpse into the CIA's 'family jewels'". The New York Times. June 26, 2007. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "Church Committee Reports, Interim Report: Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders, Book I". Assassination Archives and Public Research Center. April 26, 1976. Archived from the original on April 22, 2008.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities". www.senate.gov. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "Excerpt: "No Place to Hide"". ABC News. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013.

- ^ "Senator Sam Ervin And the Army Spy Scandal Of 1970-1971 | CMHPF.org". Preservation & Resale of Historic Real Estate Nationwide. Archived from the original on August 29, 2005.

- ^ "Military surveillance. Hearings .., Ninety-third Congress, second session, on S. 2318., April 9 and 10, 1974". Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off. December 10, 1974 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hersh, Seymour (December 22, 1974). "Huge C.I.A. operation reported in U.S. against antiwar forces, other dissidents in Nixon years" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Prados, John (2006). Safe for Democracy: The Secret Wars of the CIA. Ivan R. Dee. p. 434. ISBN 9781615780112.

- ^ John, Pastore (January 27, 1975). "S.Res.21 - 94th Congress (1975-1976): Resolved, to establish a select committee of the Senate to conduct an investigation and study of governmental operations with respect to intelligence activities". www.congress.gov.

- ^ a b Prados, John (2006). Safe for Democracy: The Secret Wars of the CIA. Ivan R. Dee. pp. 438–439. ISBN 9781615780112.

- ^ Church Committee (November 20, 1975). "Alleged assassination plots involving foreign leaders" (PDF).

- ^ Prados, John (2006). Safe for Democracy: The Secret Wars of the CIA. Ivan R. Dee. p. 437. ISBN 9781615780112.

- ^ Church Committee (1975). "Covert Action in Chile: 1963-1973" (PDF).

- ^ a b "National Security Agency Tracking of U.S. Citizens – "Questionable Practices" from 1960s & 1970s". National Security Archive. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ a b US Senate Representatives, Select Committee to study governmental operations with respect to intelligencde agencies (April 26, 1976). Book Five - The Investigation of the Assassination of President of John F. Kennedy (First ed.). Washington: US Government Office Publications. pp. 2–8.

- ^ Mary Ferrel Foundation (March 4, 2023). "House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA)". Mary Ferrel Foundation (https://www.maryferrell.org). Retrieved March 4, 2023.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Benjamin, Mark (January 5, 2007). "The government is reading your mail". Salon.com.

- ^ Prados, John (2006). Lost Crusader: The Secret Wars of CIA Director William Colby. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512847-5. p. 313

- ^ Carl Colby (director) (September 2011). The Man Nobody Knew: In Search of My Father, CIA Spymaster William Colby (Motion picture). New York City: Act 4 Entertainment. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ "The Intelligence Gathering Debate". NBC. August 18, 1975. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ Bamford, James (September 13, 2011). "Post-September 11, NSA 'enemies' include us". Politico. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ a b Andrew, Christopher (February 1995), "For the President's Eyes Only: Secret Intelligence and the American Presidency from Washington to Bush," (1 ed., HarperCollins), p. 434

- ^ Annie Jacobsen, "Surprise, Kill, Vanish: The Secret History of CIA Paramilitary Armies, Operators, and Assassins," (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2019), p. 226

- ^ Bernstein, Carl. "THE CIA AND THE MEDIA". www.carlbernstein.com. Archived from the original on October 25, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Mooney, Chris (November 5, 2001). "The American Prospect". Back to Church. Archived from the original on December 5, 2006.

- ^ Knott, Stephen F (November 4, 2001). "Congressional Oversight and the Crippling of the CIA". History News Network.

- ^ Burbach, Roger (October 2003). "State Terrorism and September 11, 1973 & 2001". ZMag. 16 (10). Archived from the original on February 1, 2008.

- ^ "Debate: Bush's handling of terror clues". CNN. May 19, 2002. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011.

- ^ Schwarz, Frederick A. O.; Huq, Aziz Z. (2007). Unchecked and Unbalanced: Presidential Power in a Time of Terror. New York: New Press. ISBN 978-1-59558-117-4.

- ^ "UK Hosts Historical Reunion of Members of Church Committee". University of Kentucky News. September 14, 2006. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008.

Further reading

[edit]- Johnson, Loch K. (1988). A Season of Inquiry, Congress and Intelligence. Chicago: Dorsey Press. ISBN 978-0-256-06320-2.

- Smist, Frank J. Jr. (1990). Congress Oversees the United States Intelligence Community, 1947–1989. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-651-6.

External links

[edit]- Church Committee reports (Assassination Archives and Research Center)

- National Security Agency Tracking of U.S. Citizens – "Questionable Practices" from 1960s & 1970s published by the National Security Archive

- Church Report: Covert Action in Chile 1963-1973 (US Dept. of State)

- Interviews with William Colby and Richard Helms from cia.gov

- Recollections from the Church Committee's Investigation of NSA from cia.gov

- Church Committee Reports (Mary Ferrell Foundation)

- Book 1: Final report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, United States Senate : together with additional, supplemental, and separate views. United States Government Printing Office. April 26, 1976. p. 391.

- Church Committee Report On Diem Coup

- Flashback: A Look Back at the Church Committee's Investigation into CIA, FBI Misuse of Power

- The Church Committee: Idaho's Reaction to Its Senator's Involvement in the Investigation of the Intelligence Community

- Central Intelligence Agency operations

- Reports of the United States government

- Investigations and hearings of the United States Congress

- Defunct committees of the United States Senate

- Lockheed bribery scandals

- Publications of the United States government

- 1975 establishments in Washington, D.C.

- Official enquiries concerning the assassination of John F. Kennedy

- 1976 disestablishments in Washington, D.C.

- Select Committees of the United States Congress